- Messages

- 2,145

- Reaction score

- 5

- Points

- 28

While science piles up astounding new findings almost everyday, underneath us the Earth is threatening to pull the rug off our feet any moment, making all these achievements that make our current civilization stand out from all the rest under threat of ending up all for naught.

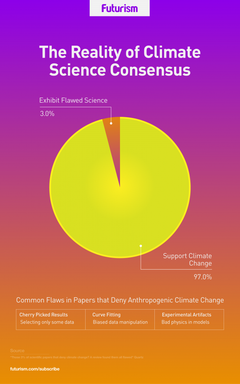

The threat of cataclysmic climate is beyond dispute. If you think otherwise, watch this thread for the mounting evidence to the fact, Trump and his kind notwithstanding.

And no—that this thread starts on Earth Day is mere coincidence. Let's just say all the half-cooked ideas and procrastination contrived to end here....

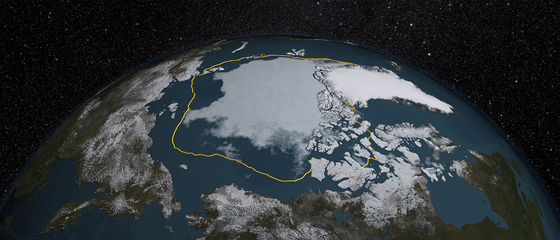

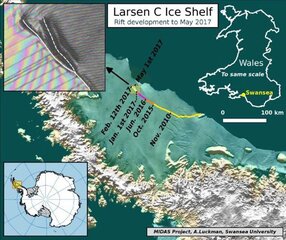

Anyway, since perhaps it's the headlines of late that finally prompted this, let's start with what's happening up there in the Arctic, encompassing such areas as the North Pole, Siberia, Russia, Greenland, Canada, the US....

7,000 Huge Gas Bubbles Have Formed Under Siberia, and Could Explode at Any Moment

What happens when the permafrost thaws.

Last year, researchers in Siberia's remote Bely Island made the bizarre discovery that the ground had started bubbling in certain places, and was squishy under the locals' feet like jelly.

At the time, just 15 of these swollen bubbles had been identified, but an investigation in the wider region of the Yamal and Gydan peninsulas has revealed that 7,000 or so of them have cropped up, and the concern now is that they could explode at any moment.

"At first, such a bump is a bubble, or 'bulgunyakh' in the local Yakut language," Alexey Titovsky, director of the Yamal Department for Science and Innovation, told The Siberia Times.

"With time, the bubble explodes, releasing gas. This is how gigantic funnels form."

Those gigantic funnels Titovsky is referring to are every bit as intimidating as they sound.

While collapsed bubbles can form fairly small 'pockmarks' in the ground, they've also been linked to the massive sinkholes and craters that have been appearing across Siberia:

Now picture thousands of these death traps dotted across the landscape, with each of the 7,000 newly identified bubbles poised to explode without warning.

So what exactly is going on here?

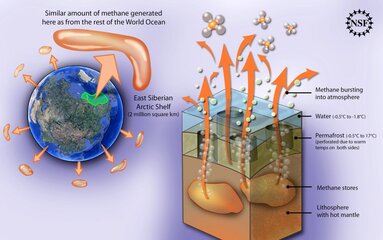

Back in 2016, local environmental researchers Alexander Sokolov and Dorothee Ehrich decided to pull back the dirt and grass that had been blanketing these bulging bumps of earth, and found that the air escaping from them contained up to 1,000 times more methane than the surrounding air, and 25 times more carbon dioxide.

And things can get even weirder at the bottom of the biggest sinkholes—a 2014 investigation into a 30-metre-wide (98-foot) crater on the Yamal Peninsula found that air near the bottom of the crater contained unusually high concentrations of methane—up to 9.6 percent.

As Katia Moskvitch reported for Nature at the time, archaeologist Andrei Plekhanov from the Scientific Centre of Arctic Studies in Salekhard, Russia, told her that the surrounding air usually contains just 0.000179 percent methane.

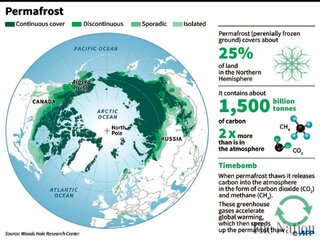

Researchers have hypothesised that these methane bubbles are linked to a recent heatwave that had prompted the Siberian tundra's permafrost to thaw.

Siberia's permafrost has become famous for its ability to keep things perfectly preserved for thousands of years, such as this amazing 12,400-year-old puppy,or these adorable lion cubs, which still had their tawny fur coats on after 30,000 years.

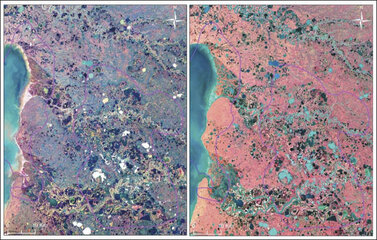

A 2013 study found that a global temperature rise of 1.5°C would be enough to kickstart an unprecedented period of melting, but thanks to abnormally hot summers linked to climate change, local researchers suspect that this is already starting to occur, with daily temperatures in July 2016 hitting a worrying 35°C (95°F).

"Their appearance at such high latitudes is most likely linked to thawing permafrost, which in is in turn linked to overall rise of temperature on the north of Eurasia during last several decades," a spokesperson for the Ural branch of Russian Academy of Science told The Siberian Times.

We're still waiting on some peer-reviewed research to come from these investigations so we can know more about the evidence scientists are using to link methane bubbles to climate change, but it looks like the unique geology that makes up the Siberian tundra also plays a big role in the phenomenon.

According to Vasily Bogoyavlensky from the Russian Academy of Sciences, who has been studying these bubbles for years now, the earth here has been dated to the Cenomanian era of the Late Cretaceous epoch (100.5 to 93.9 million years ago) and has been identified as an ancient, shallow gas reservoir, situated just 500 to 1,200 metres (1,640 to 3,937 feet) below the surface.

"Gas rising to the surface through the systems of faults and cracks causes overpressure in the palaeo-permafrost clay layers, and breaks through the weakened parts of it, forming the gas springs and blowout craters," Bogoyavlensky wrote in a 2015 edition of GEO ExPro magazine.

"Basically, after a long period of growth, the upper part of the 'pingo' (the soil covering the ice core) cracks, and the ice core melts, forming a round lake. It is known that sometimes these ice mounds explode under excessive ice pressure."

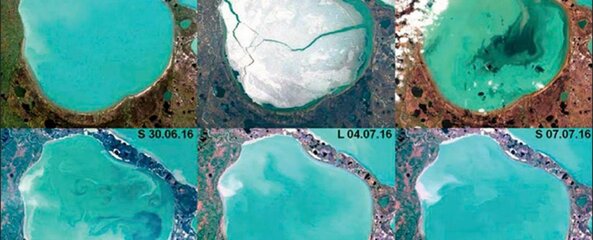

Here's an image of one bubble found by Bogoyavlensky that has swelled immensely:

And here's what it looks like if you find one small enough to step on:

The good news is that through all of this, there are several research teams out on the tundra studying this weird phenomenon, so hopefully we'll have some definitive answers soon.

To reiterate what we said earlier, published research on these bubbles is still forthcoming, and Titovsky in particular says he's not done with his field investigation yet, so we'll have to take these conclusions with a grain of salt until the results are verified.

But the priority right now is for researchers to identify which bubbles pose a threat to the locals, and provide a map highlighting the potential explosion 'hot spots'.

"We need to know which bumps are dangerous and which are not," Titovsky toldThe Siberian Times.

"Scientists are working on detecting and structuring signs of potential threat, like the maximum height of a bump and pressure that the earth can withstand. Work will continue all through 2017."

SOURCE

UPDATED: VIDEO OF EARTH with NASA'S rendition of "Sound of Silence"

Attachments

Last edited: